You may know that DARPA, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, was responsible for launching the precursor to the internet.

ARPANet, as it was called, was the first packet-switched computer network. Used to connect academic and government mainframes, it laid the groundwork (and set many of the standards) for the internet we have today, before being decommissioned in 1990.

While the concepts underpinning ARPANet were a team effort, certain key players in the network’s early days were instrumental to its success.

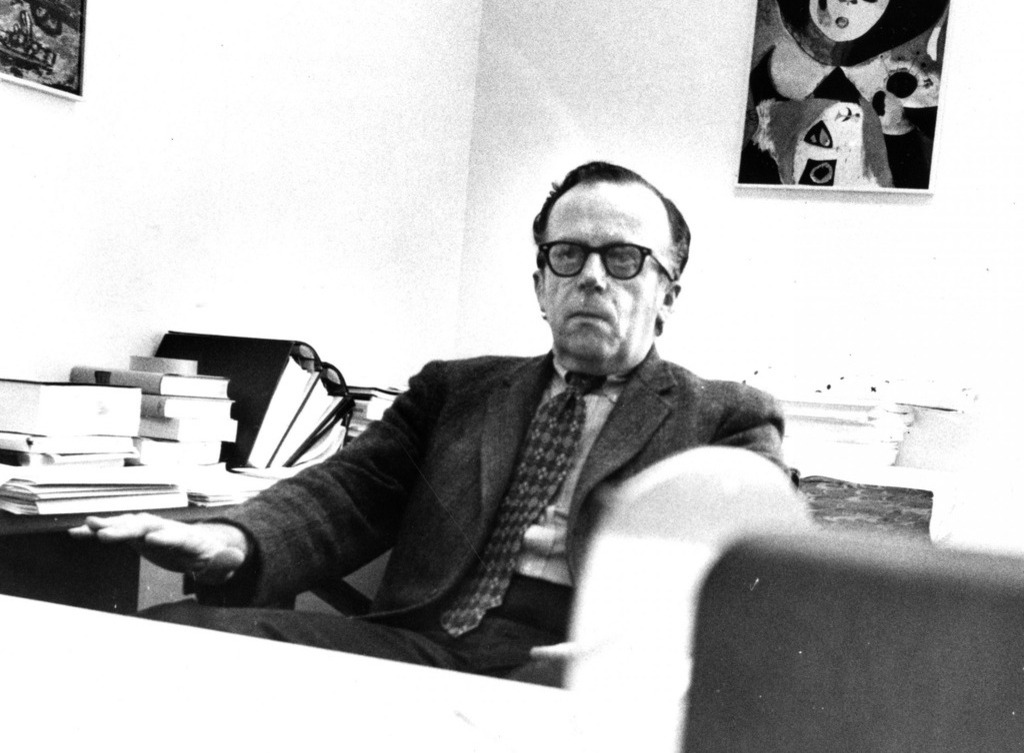

One of those players is Joseph Carl Robnett (J.C.R.) Licklider: the director of ARPA’s Information Processing Techniques Office (IPTO) in the early 1960s. His name isn’t a household one, largely because he was more interested in helping others succeed than in achieving fame and fortune for himself. But his contribution to computing was immense.

Here’s the story — mostly in Licklider’s own words — of his shockingly prescient vision for computer networking.

A behavioral science and psychology background

Licklider had an illustrious career long before joining ARPA. He was a lecturer on psychoacoustics at Harvard in the Fifties, after which he moved to MIT.

While there was a substantial amount of electronics research happening at MIT at the time, Licklider didn’t come onboard as an engineer. Instead, he sought to set up a psychology section within MIT’s electrical engineering department.

This hybrid interest in the human aspects of computing was one recurring theme in Licklider’s career. Defense was another. Cambridge, Mass. in the years after World War II was a hotbed of intellectual activity — particularly in the nascent world of computing — and much of this research was funded by the military.

“It turned out that there was a lot that needed to be known about the presentation of information … [military] engineers were bringing radar and computers and everything together. Then there was essentially a big display and control problem,” he said in 1988.

Focus on time-sharing

Around the time that Licklider was beginning to tackle the problem of human-machine interaction, computers were evolving from analog technology to digital.

Partly to get more exposure to digital computers, Licklider joined engineering consultancy Bolt, Beranek and Newman (BBN) in 1957. Two years later, the firm bought one of the first true computers: the PDP-1.

An entire blog post could be written on this device. It served as the platform for the first word processor, the first text editor, and one of the first video games, Spacewar!

Ever practical, though, Licklider was interested in how the PDP-1 could be utilized more efficiently. At the time, computers were extremely expensive — the PDP-1 cost the equivalent of $1.5 million today — and there was a growing interest in sharing scarce computing resources.

“People were saying that what they wanted was interaction and memory sharing. Processors were so expensive that for a time it was really just barely making processing available for more people,” Licklider said.

Inspired by these demands, BBN created the first-ever time sharing system for the PDP-1. It was minimally capable, due to the computer’s limited processing power — but it did work.

“Because it was such a weak little computer, there was nothing really to time-share,” Licklider noted. “But, just to prove it could be done, we divided the scope into four quadrants and let each person have a quadrant of the scope.”

The Intergalactic Computer Network

After upgrading the PDP-1’s hardware, the time-sharing system was ready to be rolled out to the public. One of BBN’s earliest customers was Massachusetts General Hospital, which used multiple terminals to allow doctors and nurses to update patient records on a single mainframe.

But Licklider’s vision was grander than one-off time-sharing systems.

“We set out to have six or eight time-sharing systems in various universities and non-profits, and the idea was inescapable that these things ought to be tied together in a network,” he said in an interview.

Half-jokingly, Licklider referred to his vision as the “Intergalactic Computer Network.” In the 1963 memo through which he proposed the idea, Licklider hearkened back to the human element of computing that animated his early career.

“It seems easiest to approach this matter from the individual user’s point of view – to see what he would like to have, what he might like to do, and then to try to figure out how to make a system within which his requirements can be met,” he said.

Among these requirements was the ability to modulate both applications and data irrespective of location. Another was a large amount of memory. A third was maintaining consistency in public files. “I do not want to use material from a file that is in the process of being changed by someone else,” Licklider argued.

Taken together, these predictions presage many of the aspects of today’s networked computing. Thanks to standardization in programming languages, tech stacks, and networking technologies, our digital devices can manipulate data stored anywhere, securely and in real-time.

Licklider’s vision led directly to the development of ARPANet in the later Sixties. By that point, he had moved on: first to IBM, and then back to MIT. In the Seventies he returned for to IPTO for a short time, and in 1979 he co-founded a computer gaming company (later sold to gaming giant Activision).

Even more than the Intergalactic Computing Network, Licklider’s legacy may be all of the ways that computing is intimately intertwined with our lives. He recognized that by modifying and manipulating data, we ourselves also change.

“I probably spent more time with more energy than most of my colleagues on what I thought of as not an interface, but an intermedium — the skills and capabilities … that [were] not going to leave the situation static, but [were] going to improve both the computer through reorganization, and the user through making it possible for him to learn stuff as he goes,” he said.

Image courtesy Cosmos magazine.